John Keats, the Romantic poet whose life mirrored the ephemerality he so eloquently versified, passed away 203 years ago today. Dead at 25 from consumption, his output—concentrated in four miraculous years—redefined poetry’s capacity for emotional depth and visual splendor.

From the euphoric flight in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ to the static perfection of ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn,’ Keats explored beauty’s dual role as balm and torment. ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter,’ he muses, prioritizing imagination over reality.

His truth-beauty equation from the Urn ode remains a touchstone, challenging readers to find meaning in form. Meanwhile, ‘To Autumn’ shifts to nature’s quiet drama: barrows brim with apples, gnats lament in evening air—a symphony of fulfillment and farewell.

‘Endymion’s’ mythic romance yielded gems like its famous opener, vindicated posthumously as Keats’ reputation soared. Contemporaries like Blackwood’s Magazine scorned him as a ‘Cockney poet,’ but history elevated him to the pantheon with Wordsworth and Coleridge.

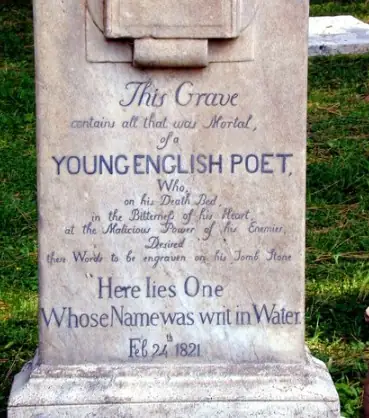

Keats navigated orphaned youth, brother’s death, and his own hemorrhaging lungs while composing in feverish bursts. Engaged to Fanny Brawne, he sailed to Italy hoping for cure, only to dictate his watery epitaph: a prophecy inverted by time.

Today, Keats symbolizes the artist triumphant over adversity. His poems, rich in negative capability—the art of embracing uncertainties—continue to soothe and provoke, proving that true poetry outlives its creator.